How Pavement Tricked Everyone Into Hating (and Then Loving) Wowee Zowee

I hated Pavement’s album Wowee Zowee on my first listen. I had never listened to Pavement before, and found the experience confusing and far too strange. Lyrics like “Pick out some Brazilian nuts for your engagement” from lead track “We Dance” and “Canyon bro', your life is worked in / Dream about the witch trials” from “Half a Canyon” felt random and disorienting. The forceful guitar parts and cutting vocals on many of the songs (especially the shorter ones) seemed abrasive and, for lack of a better way to put it, a bit much. The whole thing seemed a bit much, too haphazard and random to really enjoy.

Critics felt much the same way upon the album’s release in 1995. Rolling Stone gave the album 2.5/5 stars, dismissing it as “scattered and sloppy”, and the Guardian went so far as to say it “probably helps to be a 15-year-old boy to appreciate Pavement.” The guitar work and arranging were too heavy-handed, the new sounds and styles with which they experimented too cursory and slapdash. Pavement’s lyrics, which always teetered on the edge of nonsense (frontman Stephen Malkmus was known for just picking words that sounded good and frequently made up new lines from take to take of each song), had gone too far. After their previous album, Crooked Rain, Crooked Rain, had promoted Pavement to the status of rising indie rock darling, they seemed to have dropped the ball in spectacular fashion.

But now, people love Wowee Zowee. What happened? How did Wowee Zowee go from botching Pavement’s shot at becoming iconic to helping propel them to the forefront of 90s indie rock pantheon? A hint lies in perhaps my favorite criticism of the album, in which Details described the album as “a great band trying hard to prove they can suck, and half-succeeding.” Though they meant it as a criticism, Details unintentionally hit on what was really going on here: the frustration and confusion people felt upon hearing Wowee Zowee in 1995 was exactly what Pavement wanted.

To understand why Pavement wanted to make a disappointing album, it helps to contextualize their general attitude towards the music industry, which Malkmus had always hated. The group only ever signed with independent labels despite offers from more major ones, and even refused to interact with the press or play live shows for their first year. They didn’t even bother to publicly release their first album until well after it had circulated on cassette for a year and accrued a substantial underground following.

Malkmus also started beef with Billy Corgan (frontman of the Smashing Pumpkins) after Malkmus criticized the Pumpkins on the single “Range Life” from Crooked Rain, Crooked Rain. Though Malkmus has maintained the line was meant to be light-hearted and that he had essentially just improvised it on that particular take of the song, Corgan was upset and asked Malkmus to apologize. Malkmus, thinking the whole affair was stupid, refused. Both bands were slated to perform at Lollapalooza 1994, so Corgan issued the event coordinators an ultimatum: boot Pavement from the show, or the Smashing Pumpkins wouldn’t play. The Pumpkins were the event’s headliners and, because Malkmus still refused to apologize, Pavement lost their chance to perform at the event at all. Malkmus and Corgan didn’t smooth things over until 2018, even though they played on reunion tours at the same festival in 2010.

All this is to say, Malkmus’s relationship with the music industry was tenuous at best, and he wavered between not understanding how to deal with Pavement’s success, or just refusing to outright. So when the indie rock establishment was ready to embrace Pavement, it only made sense that Malkmus would turn away from the opportunity.

And turn away from it Pavement did. Though Malkmus claimed the songs they made for Wowee Zowee “sounded like hits,” Pavement layered these “hits” amidst yelling, distortion, and nonsense, all of which were sure to confuse upon first listen. Pavement took the arranging and lyrical skills they had honed while producing Crooked Rain, Crooked Rain, but chose to obscure them from critics who expected a more conventional follow-up by leaning into the rawness and experimentation of their initial release, Slanted and Enchanted. Pavement was making music with the expertise of musicians who had already mastered their craft, but was delivering it with the attitude of a band trying things out and messing around on their first studio release.

Pavement’s primary tool for disguising Wowee Zowee’s lyrical and musical genius was irony, which leaves its mark all over the album. Songs like “Serpentine Pad” and “Brinx Job” come across as caricatures of earlier yell-heavy Pavement songs like “No Life Singed Her” and “Conduit For Sale!,” abandoning any pop sensibilities of the latter two for more lead-footed beats, more nonsensical lyrics, and more distortion and fuzz. But their weirdness is so complete and thorough that you can’t help but love them and scream along (if you can figure out the lyrics).

The lyrics of “Fight This Generation” are also largely nonsensical, with the only really coherent part being when Malkmus repeats “fight this generation” 17 times at the end of the song. The music often simmers but never comes to a full boil, and it sits at a strange intersection between Pavement’s usual style and ‘80s nightclub techno elements Malkmus would explore further 24 years later on Groove Denied. “Fight This Generation” is unable to decide whether it wants to laugh off Pavement’s identity as an iconic, anti-establishment slacker rock group or embrace it. And despite all of this, it became one of Pavement’s most iconic songs and was often a popular closer during live shows.

Perhaps no song is as glaringly ironic on Wowee Zowee, however, as the ridiculous “Flux = Rad”. Even before hearing it, the ludicrously bad title should give away its intentions. Its only lyrics are variations of “styles / come and go / but I’m not gonna let you go,” which are interspersed between agile, banging, and distorted guitar riffs that a 14-year old would probably describe as “kickass.” And yet, it’s hard not to get swept away and start moving when the song’s insistent, grooving bassline kicks in.

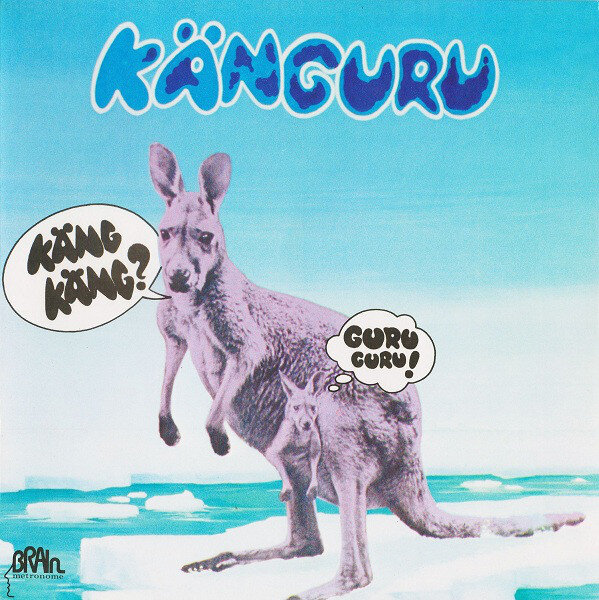

Even the album cover smacks of irony. Malkmus purportedly picked the image (before it had the speech and thought bubbles) from a stack of random paintings by New York artist Steve Keene because it reminded him of the art for the 1972 album Känguru by Guru Guru. The key thing to notice here are the speech and thought bubbles, with one of the figures saying “Pavement?” and the dog thinking “Wowee Zowee!” Malkmus seems to be directly making fun of the hype that surrounded Pavement after critics fawned over their previous release, Crooked Rain, Crooked Rain, offering the perfect context to set up Wowee Zowee’s absurdity.

So why didn’t critics pick up on all these signs that pointed to the album being a beautiful mess drenched in irony? Part of the problem was how busy 1995 was for rock (especially indie rock) as a whole. Radiohead had truly begun to explode with the release of The Bends; Oasis was taking the mainstream by storm with (What’s the Story) Morning Glory?; Blur rose alongside them with their album The Great Escape; and the Smashing Pumpkins had just released their landmark double album Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness. These albums all dramatically shifted the landscape of ‘90s rock and indie rock by introducing new styles, musical and lyrical elements, and seeing the meteoric rise of some of the genre’s most prominent groups. Critics were just too caught up in too many ground-breaking albums that year, making it easy to dismiss Wowee Zowee as sloppy and underbaked on first listen without taking the time to peel back its many layers.

Unfortunately, this dismissal means that not only did critics miss out on Wowee Zowee’s context, but many songs that could stand apart from that context as being great on their own (no irony necessary) also got lost in the shuffle. On first listen, it’s easy to get so caught up in the rollercoaster that is “Flux = Rad” that the legitimately fantastic preceding track, “AT&T,” fades from view, even with its carefully crafted lyrics about a relationship crumbling amidst poor communication and stellar interweaving of Malkmus’s voice and guitar. “Grounded,” despite having what some now regard as some of the decade’s best guitarwork, suffers a similar fate, as the listener has little time to digest it before the brazen and boisterous “Serpentine Pad,” which immediately follows it. Lyrics like “there is no castration fear” off opening track “We Dance” can be so unexpected that it becomes hard to stay focused on what is arguably Malkmus’s most beautiful and wistful vocal work. Here, we see Malkmus imagining himself dancing with someone he loves, only to find he can’t connect with anyone, or even the world around him for that matter.

But maybe the greatest thing Wowee Zowee had working against it upon its release is that it just wasn’t what people were expecting. Their previous album, Crooked Rain, Crooked Rain, had seen Pavement hone their skills and smooth down some of the rougher edges on their beloved but raw initial release Slanted and Enchanted. People expected Pavement to take the next step, to perfect and polish the formula that brought them so much acclaim with Crooked Rain, Crooked Rain. Instead, they got Wowee Zowee.

Thankfully, one way or another, the album was able to work its way into the hearts of indieheads, myself included, and is now regarded as a seminal work of ‘90s indie rock. In a strange twist of fate, Malkmus’s initially successful attempt to diffuse media attention and hype cemented Pavement as one of the decade’s foremost rock outfits, and made Malkmus himself an indie rock icon. And while some of its wackier tendencies may still be somewhat of an acquired taste, it serves as a reminder that some albums deserve a second (or even third) listen.